The date: October 6, 2025

The matchup: Pennsylvania (1-0) at Georgia Tech (2-0)

The stakes: The season just began, but the winner likely secures a claim to the mythical national title. For a team in the South in 1917, this is a pretty big deal. (It is also, in fact, a really big deal that a powerhouse like Penn would visit the South at all.)

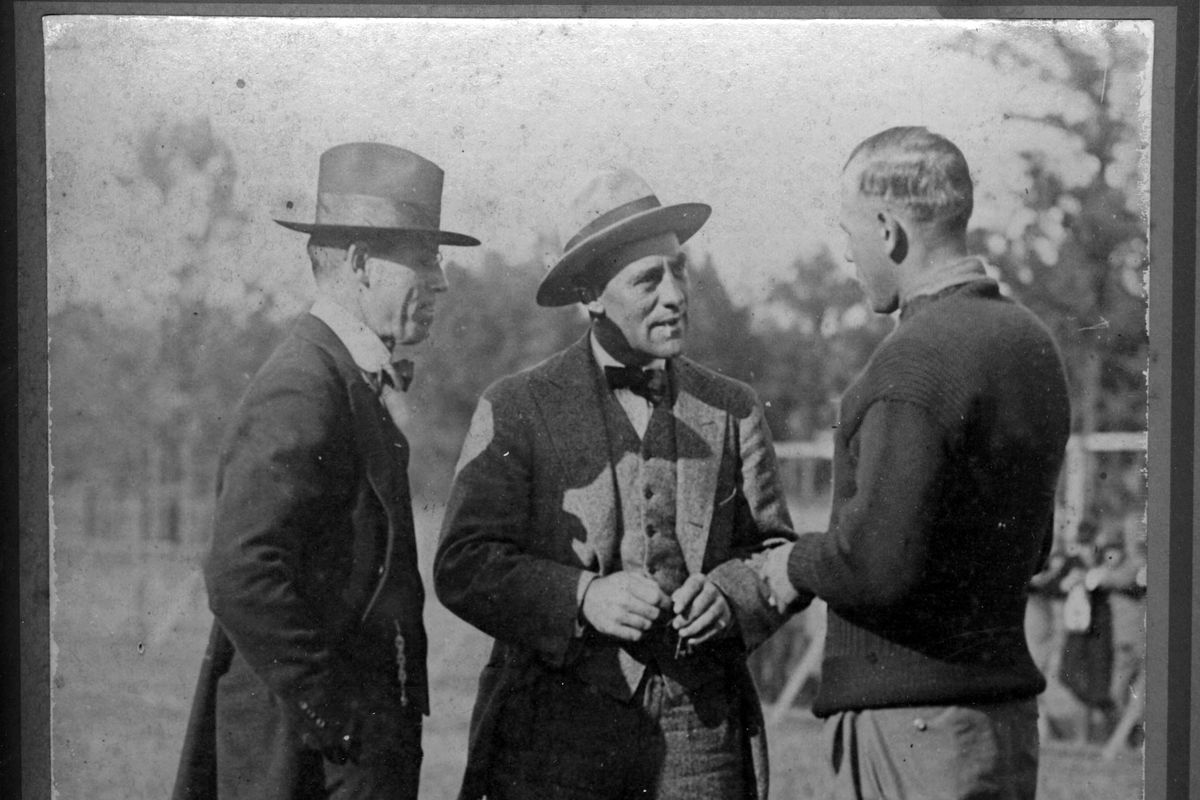

The back story: John Heisman’s Georgia Tech squad had just about achieved football perfection when 1917 rolled around. The Yellow Jackets had gone 15-0-2 over the last two seasons, outscoring opponents by a combined 654-44. In 1916, they had famously beaten Cumberland by just a couple of touchdowns. And in 1917, they added one of the best players in school history, Joe Guyon.

Guyon was good enough to dominate on the ground in 1917 and then earn All-American honors as a tackle in 1918. His presence made the jump shift ridiculously effective. From 50 Best*:

The New York Times called Heisman’s 1917 squad “such a sensation” and “unquestionably the leading eleven of the last season.” Tech was already loaded with future hall-of-fame halfback Everett Strupper (most notable for either being deaf or for scoring eight touchdowns against Cumberland in 1916), quarterback Buster Hill (the short-yardage guy), and fullback Judy Harlan. Guyon’s arrival gave the team one more weapon than any opponent could account for, especially when deployed with Heisman’s controversial jump shift.

College football offenses tend to be pretty straightforward in their labeling. Defenses can take you pretty far down the road of green dogs and quarter coverages and C-gaps, but offenses don’t try to fool you. The spread offense is an offense that tries to spread you out. The wishbone is a backfield with backs arranged to look like a wishbone. And the jump shift was literally a method for offensive players to shift by jumping in unison.

That might sound a little bit primitive, but it worked to devastating effect for Heisman’s offense. The quarterback, fullback, and halfbacks would line up in a straight line behind center – a dotted-I formation, if you will. In unison, the three backs who wouldn’t be carrying the ball would shift in one direction or the other, creating an impromptu wall behind which the ball carrier-to-be could run. It was a primitive version of the single wing, and it helped to assure that the offense had more bodies at the point of attack than the defense.

Tech was so precise in its jumping and shifting that opponents swore the Yellow Jackets were cheating.

This was a controversial formation because some thought it allowed the offensive players a running start. This was not a nationally televised sport, obviously, so word traveled via mouth and newspaper, and it didn’t quite seem kosher. But in a letter written to the Washington Herald in 1918, Heisman emphasized that the pause before the snap made it legal, noting, “we have employed it in each of our games from 1910 in which some of the most famous officials in America have been involved – and not one has found fault with it.” A fair point.

It’s hard to imagine Tech generating any more of an advantage in 1917 by cheating, though. The Engineers were absurdly good. And they proved it when powerful Penn came to town. Against teams not named Tech, the Quakers would go 9-1 with a scoring margin of 245-30. Pitt was assumed to be the best team in the country, and Penn fell to the Panthers by only a 14-6 score. Tech beat them by just a little more than that.

The game: From the New York Sun:

ATLANTA, Ga. — The Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets ran roughshod over the University of Pennsylvania eleven here this afternoon, snowing under the Quakers, 41 to 0. Two touchdowns in the first and third quarters and one in the second and fourth were Georgia's scoring mediums.

Strupper, Guyon and Hill smashed through the Pennsylvania line at will, the first named reeling off a 70 yard run in the opening three minutes of play for the first touchdown of the game. These three backs carried the brunt of the Yellow Jacket attack and they performed their duties nobly.

Berry, Dell, Miller and the other highly touted Penn stars were stopped by the Tech defence, the sturdiness of the Georgia defence being in keeping with the brilliancy and speed of their offence. There was little doubt of who would win the game after the first few minutes, and it was then only a question as to the size of the score.

This was a walloping, and it began almost immediately.

The box score: I couldn’t find stats for this one, as most box scores in 1917 only featured lineups. Bummer.

The win moved Tech to 3-0, and after a hungover performance against Davidson the next week (the Engineers pulled away late to win 32-10, but it was closer than it should have been), they further proved they were the best team in the country. Washington & Lee, Vanderbilt, and Tulane would all finish with winning records, and Tech outscored them by a combined 194-0. GUH. And after an embarrassing 98-0 win over lifeless Carlisle, they pummeled one-loss Auburn, 68-7.

This was easily one of the greatest teams of all time, and after this pasting of Penn, it became only more clear.